|

|

|

Itinerary - Kunene

Trail - Desert Trail -

Rockart

Trail - Ethosha

- Preparations - Namibia

Home

- Cover Page

-

Kaokoland and Damaraland

An Introduction

It is a sad fact that there is no place in Africa that is as wild as it was a hundred years ago. Indeed, every single square meter of the continent has been mapped by the rowing eyes of a hundred orbiting satellites. Even fifty years ago, colonial administrators, geologists and surveyors had tramped over the whole of Africa and yet, half a century later, we are still searching for 'wilderness' as though it still really exists.

What is wilderness? For one thing, it is a definition that has been abused and appropriated by the tourist industry to describe places that ceased to be true wilderness fifty years ago - the Kruger National Park, for example. These places are not wildernesses - rather, they are theme parks, biological fanfares, where modern explorers traveling in groups experience the wonders of African bush through the air-conditioned vehicles or from the balcony of a lodge.

However, there are still a few corners of Southern Africa where the word 'wilderness' manages to retain just a little of its original meaning. The deserts and mountains of the world are always the last to be settled, so it is no surprise that nearly all of southern Africa's last wild places lie within the bounds of the Kalahari and Namib deserts.

Not for much longer though.

Seeking the wilderness myself, I realized that if ever there was a time to do all the things that I had been putting off over the past years, it was now. If I wanted to see the wilderness of Kaokoland and Damaraland before they were tamed with electrical lights, tarred roads and shopping centers and tourism - I had better get a move on and do it.

In a remote corner of south-western Africa is a desolate paradise that few outsiders have ever heard of, and fewer still have visited. The Nama and Bushmen people who once inhabited parts of this coastal desert called it "Namib", meaning endless expanse. Unlike foreign travelers who feared its terrifying desolation, they were able to survive, knowing the location of secret springs and food sources. The Namib covers an area of over a hundred thousand square kilometers, most of which is an uninhabited wilderness of sand dunes, plains and mountains. Man's role in this land has usually been confined to that of visitor. Here the forces of nature reign supreme.

The desert begins in southern Angola and stretches 1,300 miles down the Namibian coast, until it peters out at the Oliphants River in Namaqualand, South Africa. Its desert shore is known as the Skeleton Coast due to the many ships that have been wrecked there over the centuries.

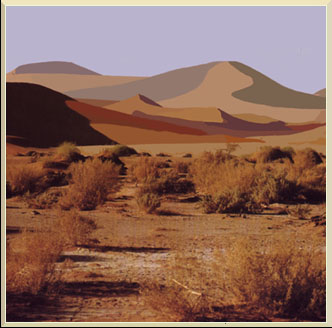

When I think of the Namib it is the sand, harsh landscapes that fills my memories and imagination, for this area is home to some of the world's highest sand dunes. There are two main dune fields. The largest of these blankets a vast tract of country between the Orange River and Walvis Bay, while the smaller one stretches northwards from Torra Bay to the Angola border. Here the dunes are halted by the fast flowing Kunene River.

The desert can be bleak or beautiful depending on the weather prevailing.In fog or cloud the dunes present a gray, forbidding backdrop, yet in evening sunlight they glow with the intensity of living coals. The sands inland are redder than those at the coast. The Kalahari sands, to the east of the Namib, are reddest of all. In the Namib the colour of the sands may change dramatically in the coarse of a single day. At the same time, the long dark shadows of the early morning and evening gradually condense, disappear and re-emerge in a different afternoon configuration.

These mountains of sand are not inert or static, but dynamic, always moving and changing, depending on the strength and direction of the wind. Some are big, some small, some fast moving some slow. Some are highly mobile, moving over fifty meters a year swallowing up anything that happens to be in their path.

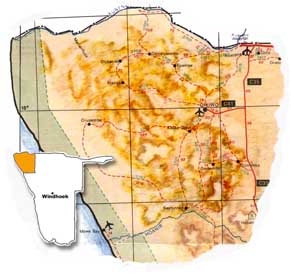

The highest formations in the Namib are the 'star dunes' near Sossusvlei, whose shape has resulted from winds blowing from several different directions. These are the slowest moving dunes, their bases stabilized by tussock grass and other vegetation. Between the Hoanib and Kunene Rivers is Kaokoland, a vast tract of country over fifty thousand square kilometers in extent, one of Africa's least known but most beautiful areas.Criss-crossed with rugged mountain ranges and deep valleys, it also boast plains as vast as East Africa's Serengeti. Prior to the 1970's, much of Kaokoland fell within the Old Etosha Pan Game Reserve. In those days the Reserve stretched all the way to the Atlantic coast, making it one of the biggest in the world, but the western area has always been closed to tourism. Since the Bush War between SWAPO and South Africa, Kaokoland has become more accessible and much of the western region has once again been proclaimed a reserve. Until very recently outsiders were not allowed in without special permission from authorities. This was because there were few roads and the region is wild and inaccessible. For many years the north-eastern part of the Kaokoland was regarded as the 'Operational Zone', and for more than twenty years of war it has been a high risk area.

One of the wildest and most spectacular parts of the Kaokoland is the mountainous area where the jade green Kunene winds its lonely way through a desolate valley, often thousands of feet deep, separating Namibia from Angola. Along the Kunene River lies the dynamic series of cascades known as Epupa Falls.

The name 'epupa' is a Herero word for the spume created by the falling water. The palm fringed river flows broad here, with several islands on which statuesque baobabs grew.

The silvery surface of the water reflected the brilliant sunlight, and spray hung continuously in the air, adding a touch of drama to the scene.

All around us were bare red mountains, their contrast turning the valley into a lush oasis. In comparison to other stretches of the river, here the Kunene really looks like a major river that has flowed for a thousand kilometers from it's source in the Angolan highlands.

Here, at Epupa, the river fans out into multiple channels and is dispersed into a series of parallel ravines. The river drops a total of 60 meters over a distance of about 1,5 kilometers. The greatest single drop is about 37 meters. It falls into a dark cleft and resembles a mini Victoria Falls.

On top of a nearby bare and rocky hill overlooking the falls before sunset, one is greeted by the setting of an amphitheater of bare, gold-red mountains through which the broad river flows, its green banks fringed with trees and palms. An absorbing landscape, which seems to bridge the gap between fairy tale and earthly reality. The beauty and the fantasy combined to weave a tapestry of magical shapes and impressions.

Impressive mountain ranges like the Hartmanns, Otjihipus and Baynes, dominate the barren landscape; in the west the Hartmanns merge with the dune sea.

Normally this is an austere world of rock and sand but occasionally rain falls. On these rare occasions the valleys are transformed into paradise, carpeted in dense grass with wild flowers and huge congregations of springbok, gemsbok, ostriches and giraffe. Gradually the grass dries out and dies, turning from lush green to gold, rippled into thousand different patterns by the wind. Even the secretive mountain zebra zigzag down from rocky passes to join the party on the plain.These plains and mountains are the home of the Himba people, tall independent nomads who live in isolated communities, tucked away in remote valleys. Like the wildlife of the region, they move as the rain and grazing dictate, leading their cattle and goats to ancestral water holes. Unlike their Herero cousins, whose flamboyant style of dress was influenced by the wives of early missionaries, they dress traditionally, in skins. The women use ochre make-up like the Maasai in East Africa.

The Himba are a nomadic offshoot of the Herero people who, according to anthropologists, migrated south from East Africa about three hundred years ago. During the last century they moved south into present day Namibia, one group settling in the central highland region, where they came into contact with the first missionaries, from whom the Herero women adopted their colourful Victorian style of dress. The other group, later known as Himbas, settled in the arid areas of Kaokoland. Out of contact with the western world, they have successfully preserved their traditional lifestyle to this day.

Himba boys wear the traditional leather apron and the metal beaded collar that all the men appear to wear. Their heads shaven except for a central strip of hair which is plaited into a single pigtail at the back. When they get married they have to wear their hair longer, and keep it all wrapped in a large turban of cloth or softened sheep skin. One often sees a skewer behind their ear, which they use to scratch under the turban when their coiffure gets itchy.

Himba girls wear their hair in two plaits hanging over the forehead. When they get married they wear their hair lengthened into long thin braids. On the top of their heads is a soft skin headpiece signifying their married status. Their bodies are always adorned with necklaces and belts, and a special white conch pendant that hangs between their bare breasts.These shells are traded through Angola, having originally come all the way from the east coast of Africa, and are usually the women's most treasured possessions. Most striking of all, are their spiral copper armlets and iron beaded anklets. Beautiful soft buck skins hang from their hips.Himba women are smeared from head to foot in a mixture of butter and ochre. Undisturbed by the decidedly rancid smell of this cosmetic, they consider it essential to their appearance and claim, furthermore, that it protects them from the sun's piercing rays. For good grooming, every part of the body and every item of dress must be anointed with this mixture which is worn by men and women alike.

Sandals of leather protect their feet from the baking sand and European belts and a T-shirt are obvious innovations of modern time; but the women tend to dress more in their traditional clothes than men.The Himbas' lives revolve around their livestock, their cattle in particular. Cattle are still the main indication of wealth and status in their society, but they do not normally eat them, slaughtering them only for special ceremonies such as weddings, name-givings, circumcisions and funerals.

A Himba chief's grave is surrounded by stone, stout poles and the horns of cattle sacrificed at the funeral. To ensure that the spirit of the sacrificial beast does not escape its body when the mourners break its neck with their bare hands, its nostrils are stuffed with grass and clay and its mouth held shut. The dead person's body is bound up in the raw hide and lowered in a crouching position into the grave, together with his personal belongings. The mourning that follows is long and uninhibited, and to ensure that the ancestors welcome the new member into their ranks, offerings of raw meat are made. Once the funeral rites are over the grave becomes a solemn shrine, the ground hallowed and the place one of worship.DAMARALAND

South of the Hoanib valley is Damaraland, a rugged rock-strewn wilderness cut through from east to west by sand rivers. These are a special feature of the Namib, dry watercourses that only rarely flow after exceptional rainfall. Even when they do it is normally for two or three days at most. Under the surface these linear oases may flow for much longer, and underground pools and moisture can persist for more than a year, enabling plants and shrubs to survive. Damaraland's major sand rivers are Uniab, Huab and Ugab, whose valleys and tributaries are the last retreat of Namibia's desert elephant and rhino. To see these leviathans crossing the bare lava desert, or negotiating the dunes near Hoanib delta, is one of the greatest sights the Namib has to offer.

South of the Ugab River, Damaraland is dominated by a huge hulk of a mountain, the Brandberg, whose red rock faces glow like embers at sunset, visible from far around. Its hot, inaccessible valleys are a 'gallery' of ancient rock art and rare flora. The paintings were made by Bushmen who lived in the Namib for thousands of years. The desert held no fears for them and they left a vivid record of their lives and dreams in the caves and rock shelters of their mountain world.

In the central mountains of Damaraland is a place called Twyfelfontein, which means 'doubtful spring'. The hillside here is covered in large red boulders, many of which have been decorated with thousands of beautiful engravings, mostly depicting animals such as eland, rhino, giraffe and lion, painstakingly pecked out of rock. Twyfelfontein ranks as one of Africa's most important rock art sites, with the Tsodilo Hills in Botswana, and the Sahara's Tassili Plateau. A beautiful panel, 'dancing kudu', combines animal representations with schematic designs.

As if charred by some infernal fire, the Burnt Mountains continues to puzzle visitors and scientist. Rising to 200 meters near Twyfelfontein, its crudely shaped formations of red rock are inexplicably streaked with vivd areas of black, white and gray.

South-west of Twyfelfontein lies the Doros Crater, where interesting fossil remains and traces of copper have been found among the rocks. Around the Doros towards the Ugab River is the protective home of great number of Africa's most endangered species, the Black Rhino.

Damaraland is perhaps best known for its Bushman painting, the White Lady of the Brandberg,further south. The awe-inspiring mountain massive with its highest peak Konigstein, at 2,574 meters makes the Brandberg the highest mountain in Namibia. Around 120 million years ago the area was a volcano set in vast plateau of volcanic rock. Subsequent erosion of the surrounding lava gradually exposed the massive chunk of weather resistant granite which eventually also provided the numerous overhangs used as shelters by the Bushmen.The mountain became famous after the discovery of the White Lady. During the course of which many more paintings have been discovered. The accepted theory on the White Lady is that it was neither "white" nor "female" but rather a male medicine man wearing body paint.

South-west of the Brandberg with its stark and awesome landscape lies the mysterious looking Messum Crater, a secluded volcanic feature in the Gobobose Mountains. The old volcanic crater has the shape of two overlapping concentric circles with a diameter of 22 kilometers.

Along the hills grows the Welwitschia mirabilis, Namib's weirdest and most wonderful plant. Described as a living fossil and a botanical enigma. This prehistoric relative of the pine has two great leathery leaves, which grow from a massive turnip like stem. As the plants gets older these leaves become frayed by the desert winds and split, giving the appearance of many leaves.

The largest specimens are known to be well over a thousand years old, possibly nearer two thousand.

You need time to visit these regions as distances are vast and perhaps several return journeys may be required. Very little luxurious accommodation is available and you need to prepare yourself to sleep under the African stars.